Dr. Keith Hamel, Chair and Professor of Composition in the School of Music, has long been recognized as a pioneering force in Canadian music. His groundbreaking work in computer music and composition is featured on several acclaimed recordings released by Centrediscs and Redshift Music Society. As Professor Hamel prepares to retire, we reflect on his remarkable 38-year teaching career—one that has shaped and inspired many of the Canada’s most outstanding composers.

We caught up with Professor Hamel to hear how progressive rock music ignited his passion for computer music, and to learn what continues to excite him about the evolving world of music technology.

Join us for a concert to honour Keith on Friday, May 23, 2025, 7:30pm at Roy Barnett Recital Hall.

What is your origin story as a composer and teacher? Who were your mentors?

When I started playing classic guitar at age 16, I became fascinated by chord structures, chord progressions, and music theory in general. It wasn’t long before I started writing my own compositions that were closely connected to the music theory I was studying: sonatas, fugues, 2-part inventions, etc. Eventually, I started to explore non-tonal music structures and developed a personal composition language. My strong interest in mathematics attracted me to the mathematic logic inherent in music theory and composition. I have been fortunate to work with some amazing composition teachers: Clifford Crawley and Istvan Anhalt at Queen’s University; and Leon Kirchner, Earl Kim, Donald Martino, and Peter Maxwell Davies at Harvard University. These composers had different styles and approaches to composition, but I learned something valuable from each of them, and I often find myself passing on their wisdom to my students. From Peter Maxwell Davies, I learned that quality is far more important than style; there is good music and bad music in every genre, school, or style of composition. Our goal, as composers, is to strive to make the music as perfect as we can regardless of who it is for or what style we decide to write in. Davies had complex esoteric works for top-tier new music ensembles and orchestras, and pieces he wrote for the local community players on the Orkney Islands where he lived. For him, these were equally valuable works of art and the notion of “high art” and “low art” didn’t exist for him—there was just “good music” and “not so good music” and our objective was to always write “good” music. This led me to being eclectic as a composer—I will write in completely different styles depending on the commission or the performers I am working with.

Touch by Keith Hamel (2014) performed by Megumi Masaki

Tell us about your early days teaching at the UBC School of Music. What have been the most significant changes that you have experienced?

When I started teaching at UBC in 1987, I was teaching more Theory than Composition. Over time, and especially as Computer Music and Music Technology became a more significant component of music education, I shifted to teaching Composition and Computer Music (the theorists were probably just as happy not to have a composer teaching their theory courses). The most significant change over the last 38 years has been the role that technology plays in the field of Music Composition. Composition students today find it difficult conceiving of a time when there was no notation software, no digital audio workstations, no software samplers, and no YouTube. When I was a student, scores were copied by hand, and recordings of contemporary music were only available on LPs in the library. In fact, I started developing music notation software as far back as 1985, so I, and other composers, would be able to notate and print their scores rather than engrave them by hand. I still use my program, NoteAbilityPro, for my scores and to control my interactive computer music performances.

Overdrive by Keith Hamel performed by the UBC Symphony Orchestra, Jonathan Girard conductor

How did your interest in the intersection between live performance and computer electronics begin? How did your research evolve over time?

As a teenager, I loved the music of progressive rock bands who used electronic sounds (synthesizers, sound effects, guitar pedals, and audio processing) in their music and live performances. I think those rich, evocative, and electronic sounds of King Crimson, Pink Floyd, Yes, and Emerson, Lake & Palmer drew me towards computer music, and I sometimes hear the faint shadows of progressive rock music in my compositions. I started dabbling with computer music while I was still an undergraduate student in the late 1970s, and I continued working at the Experimental Music Studio at MIT while I was a graduate student at Harvard. In those days we worked on mainframe computers (i.e. the ones that filled a room and took many hours of computation before you could hear the sounds you had created). By the end of my graduate studies, personal computers were finding their way onto the market when I ordered a Macintosh computer, first released in 1984. It was a colleague and friend of mine at MIT, Miller Puckette, who developed the Max program (now called Max/MSP) that enabled composers to create interactive computer music environments. I have used this software to create my computer music works for about 40 years. While Max was very limited in its first few iterations (personal computers were so slow), it is now an incredibly powerful tool for creating live interactive audio/visual performance environments. I have also been involved in the development of music notation software and in score-following technology research. Score-following allows a live performance to be tracked and synchronized to a score in the music notation software that I developed, NoteAbilityPro. Score-following research was mostly done at IRCAM in Paris—a place I have visited many times and where I have collaborated with some amazing researchers. In recent years, I have added the Unity Gaming Engine to my composition process, and this software allows me to develop visuals that respond to the sounds and gestures made by performers in order to create interactive multimedia works.

“I think those rich, evocative, and electronic sounds of King Crimson, Pink Floyd, Yes, and Emerson, Lake & Palmer drew me towards computer music, and I sometimes hear the faint shadows of progressive rock music in my compositions.”

What advice do you have for students pursuing a career in composing, music technology or teaching? What is it that you wish someone had told you?

One thing I stress with my students is that being engaged in the community is vitally important, both to their own futures as composers, but also for the health of contemporary music more widely. I encourage my students to go to as many concerts as they can, to become involved in the contemporary music scene, and to collaborate with performers and other artists. The second thing I tell my students is to develop as much breadth as a composer as they can. Write for a wide range of instruments, explore writing for non-western instruments, get involved with computer music, live electronics and multimedia, look for opportunities to write for media, write choral works, write works that involve improvisation or graphic scores, etc. Thirty or forty years ago composers could write one genre of music in one style, but today it is hard to know where the next composition opportunity will come from. Being adaptable and capable of taking on any compositional challenge that comes your way, is going to be increasingly important for composers.

One thing I wish I had been told as a young composer was to keep my performing “chops” up rather than putting all my energy into composition and computer programming. Remaining active as a performer can have advantages for a composer, especially if you can collaborate with other performers and perform your own work.

“One thing I stress with my students is that being engaged in the community is vitally important, both to their own futures as composers, but also for the health of contemporary music more widely. I encourage my students to go to as many concerts as they can, to become involved in the contemporary music scene, and to collaborate with performers and other artists.”

What excites you about music technology and electroacoustic music today and where it is headed? How do you think AI will impact music and composing music?

It is astonishing to see the dramatic changes in computer technology over the past 40 years, even over the past 5 years. I think the fields of multimedia, virtual reality, augmented reality, and realities not yet invented will see incredible advances over the next decade. I suspect there will be a shift away from conventional music concerts and towards integrated multimedia events and artwork that only exist online. My hope is that live performance (with human performers) will still remain a vital part of music-making in the future. I still believe that there is something magical about a live performance with an audience experiencing the music together.

“I still believe that there is something magical about a live performance with an audience experiencing the music together.”

Artificial Intelligence is providing astonishing advances in how computers can replace activities currently done by humans. I expect that AI will have a profound impact on almost every facet of our existence in the future. AI will absorb some of the activities that are currently done by composers. I suspect that much of the film music and gaming music that is currently done by humans will soon be done by AI (and possibly a lot of popular music as well) However, contemporary art music is likely to withstand the assault of generative AI longer than some other styles and genres There is no financial gain associated with generating contemporary music, because it is less formulaic than some other styles, and because it is still strongly connected to the composers’ musical personalities. I don’t think generic contemporary chamber music will interest many people, but a new work by a composer who is part of your music community might.

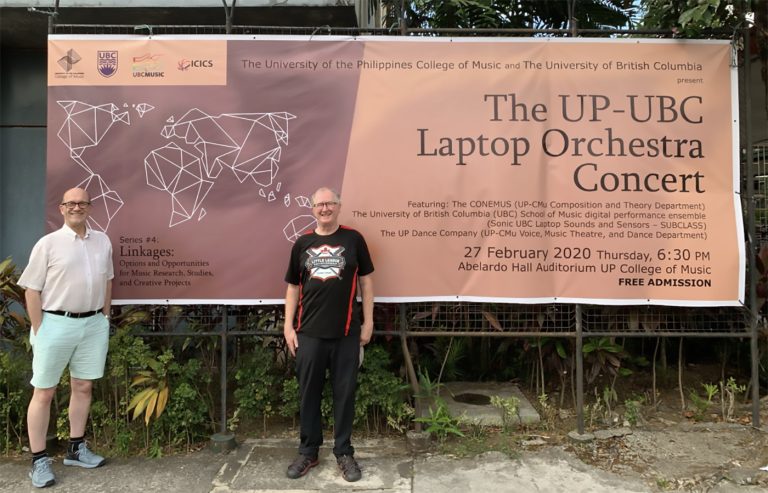

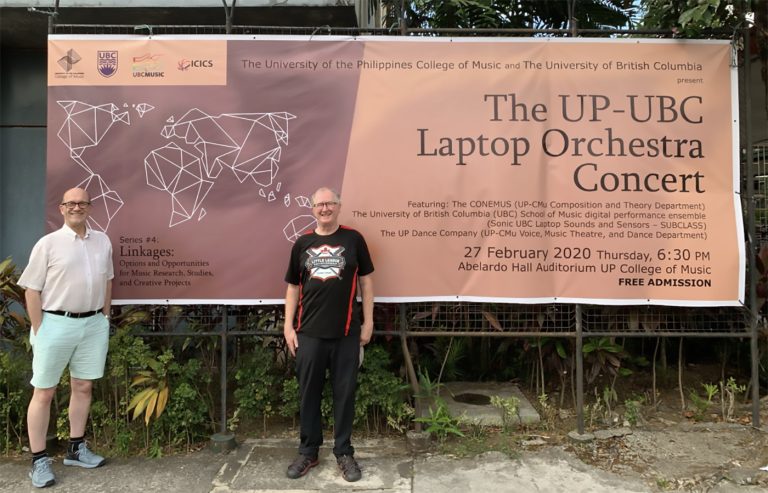

UBC Professor Emeritus Dr. Bob Pritchard with Dr. Keith Hamel in Abelardo Hall, UP College Of Music, Quezon City, Philippines (Laptop Orchestra Tour)

What are some of your most memorable experiences teaching at UBC School of Music?

I have had the opportunity to work with a huge number of extremely talented, imaginative, and creative students over the past 38 years at UBC. These include undergraduate and graduate students in Composition, and students in the Laptop Orchestra and in the Applied Music Technology program. I have always believed that teachers learn a lot from their students, and I have learned a ton from mine as we bounce ideas off one another, talk about new ways of conceiving musical form, or analyze the dramatic structure of a work in progress. The composition students that I have taught over the years have made remarkable contributions to contemporary music in Canada; so many of them are actively involved as professional composers and as professors at universities around the world. Nothing gives me more satisfaction than going to a concert and seeing the names of my former students on the program. When I see this, I like to think that at least a bit of the knowledge, or the enthusiasm for the creative process has taken root in the students. It also tells me that despite the challenges of living in a society that doesn’t value contemporary music as much as I think it should, these composers are committed to having their voices heard and creating beautiful, evocative, and innovative works that serve to strengthen the discipline, and fortify the contemporary music community.

The faculty at the School of Music (past and present) includes some of the greatest musical minds and most talented musicians that anyone could dream of working with. I appreciate the collegiality, the sharing of ideas, and the collaborations with these amazing scholars and artists. It has been a joy to work with so many of these remarkable people. In terms of memorable experiences from my years at UBC, I would have to mention the trips that Professor Emeritus Bob Pritchard and I took with the Laptop Orchestra: to Belgium, to Yorkshire, and twice to the Philippines. Bob has been an incredible colleague, and I am very proud of the Music Technology program that we built together at UBC.

“The composition students that I have taught over the years have made remarkable contributions to contemporary music in Canada; so many of them are actively involved as professional composers and as professors at universities around the world.”

What projects are you working on now? What are you excited about?

My current project is an interactive video game that will be presented in a live concert by two performers (piano and marimba in the first iteration). The two performers will be controlling two characters in the game who are in a marathon race against each other. Musical gestures by the performers control the actions of their corresponding player on the screen as they race, jump, and toss objects at each other. There is even going to be a section of the composition where the audience can interact with the game using an app on their phones. My grandchildren are helping me design the video game, so it should be fun for the audience and very challenging for the performers (as well as the computer programmer).