Dr. John Roeder has filled many roles at the School of Music as a music theorist, analyst, mentor, teacher, administrator and Chair of our Music Theory Division. His contributions and influence are immeasurable.

We caught up with Dr. Roeder to collect his thoughts about his life’s work, how he discovered music theory through science, and what excites him about music technology today. Following this interview, read comments from past students and colleagues who reflect on Dr. Roeder’s devotion, brilliance and acumen.

A symposium to honour of Dr. John Roeder will be held on Saturday, June 24, 2023 (9:30 a.m. to 5 p.m.) at the GSS Loft, AMS Nest, at UBC and online. We ask all interested to attend in-person, to register as lunch will be provided. Please visit the links below for details, program and how to register.

Dear UBC and Vancouver music community,

On Saturday June 24 from 9 AM to 5PM PST, the UBC School of Music will host a daylong symposium in honour of Professor John Roeder, who is retiring after 38 years of teaching, research and service. Professor Roeder’s contributions to the analysis of contemporary Western art music, the study of rhythm and meter, transformational analysis, and many modes of theorizing have been immense. His work in the theorizing of musical cycles and analysis of many musics from around the world have been formative in ethnomusicology as well. He is dear to his many colleagues and students, admired for his superb teaching and selfless service to his many communities.

For the symposium 10 of Professor Roeder’s graduate advisees from across the decades will return to Vancouver to present their latest research in his presence on a wide range of topics (Including pedagogy, composition, world music traditions, popular musics, and much more). Please visit this link for a complete program and information on location, schedule, and how to register for both in-person and remote attendance. (Lunch will be provided for those attending in person, but we need a head-count in advance.)

We hope to see you either in-person or online!

Kind regards, your hosts Michael Tenzer, Leigh van Handel, and Oscar Smith

What is your origin story as a music theorist? Who were your mentors?

I came to theory through composition and science. I liked to put notes together since I was about nine years-old, when my piano teacher showed me how to notate my first piece. As I took piano lessons, I was especially drawn to the bold Beethoven sonatas but also pieces by 20th-century composers. I’d browse the local music store to find new music to play. I wrote many musical-style songs in high school, as well as a few serious pieces. Composition was a bit of a side gig, though, since I was also good at physics and computer science, so I began college in 1973 to focus on them (it was an exciting time in both computer science/AI and particle physics, and as a research assistant I even got my name on a published physics paper).

But I took music major courses as well, and volunteered as classical music librarian/producer/announcer for the local college radio station, all of which exposed me to a very wide range of music. One day, my theory prof Luise Vosgerchian said, “If you can’t go a day without thinking about and making music, maybe you should become a music major.” So I did, and started taking composition lessons and upper-level courses in theory and analysis; my graduating thesis was a string trio inspired by Ligeti’s second quartet.

I applied to graduate schools in both composition and theory, but my composition portfolio was pretty slim and I think my teachers saw that my scientific ways of thinking suited me better for theory, so I entered the PhD program at Yale. I was very fortunate that the faculty there—Allen Forte, Claude Palisca, and my thesis advisor, David Lewin—were preeminent; theory as a discipline separate from musicology and composition was just crystallizing, and they were defining the field. I’ve been inspired by many other theorists as well, especially by the deep thinking and lucid prose of my two mentors at UBC, Wallace Berry and William Benjamin.

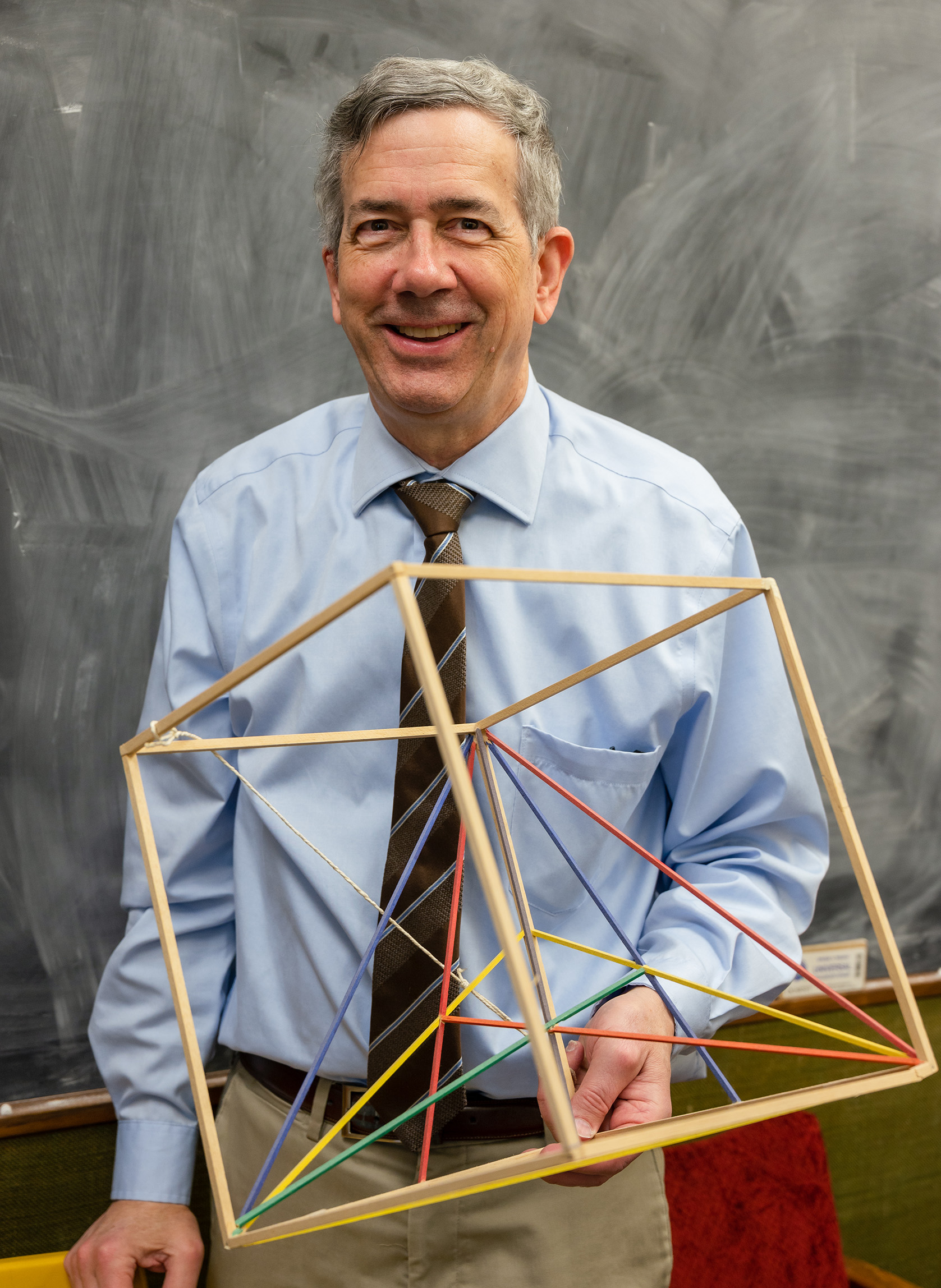

Hanging over my desk is this wooden cube that explains why there are exactly 29 different kinds of 4-note chords and which ones can be connected most smoothly. - Dr. John Roeder

Photo credit: Felix Rowe (BMus '23)

Tell us about your days as a student. What parallels do you see between being a student in the 70s, and being a student today? How do you see student life being different?

In many ways my experience at a small liberal-arts residential college in the early 1970s differed from that of today’s students in UBC’s professional music programs. I didn’t have to cook my own meals or commute to classes, I took only four classes per semester and had time for extracurricular activities. Yes, I was spoiled.

I admire the energy and drive of UBC students, and I think they are getting a lot for their hard-earned tuition. The basic purpose of higher education hasn’t changed that much. Students need time to explore new ideas and disciplines, figure out what they are good at, and practice the core values of scholarship and society. It has always been vital to hear, play, and think about as much music as possible. The challenge today is information overload, with so much knowledge and music instantly accessible anywhere. More than ever, we need wise teachers to direct our learning towards music that shows craft we can emulate and that means the most to its listeners.

How did your research evolve over time? What are you interested in now?

At first, I concentrated on describing systems of musical pitch in formal terms. Hanging over my desk is a wooden cube that explains why there are exactly 29 different kinds of 4-note chords and which ones can be connected most smoothly. I also wrote computer programs that analyze music into hierarchical layers, and that facilitate visualizations of motivic relationship.

Over time these interests converged in several papers about transformation theory—which treats the piece in terms of its musical “objects” changing in time—and about representing transformations using animations and interactive graphics. I became especially interested in exploring how these concepts could help explain concert music of living composers from Europe and the US (Saariaho, Adès, Torke, Pärt, Kurtág, Adams) and China. But I have also been keen to theorize musical rhythm, especially in post-tonal music. I described how some music can be conceived as involving two or more different pulse streams going on at once, and how to understand rhythmic shaping in music that is continuously changing with little repetition. In the last part of my career, collaborating with my inspiring colleague Michael Tenzer, I had been analyzing traditional music from around the world, appreciating the special rhythmic experiences it affords.

“I think we will start hearing music generated by AI that will challenge our notions of musical originality, intellectual property, and artistic value.”

What are your thoughts on the current musical landscape? Do you see art and music becoming more political now?

With the advent of the internet, there are just too many music subcultures today for me to generalize about. In all genres I listen to, including classical, jazz, and popular, I feel that there are musicians that are true artists, as great as we had in the past. Some treat political and social issues, as many great artists have. But that was certainly the case in the years I was a student, when there were also terrible wars, inequalities, and environmental crises.

What excites you about music technology today? How do you see it changing in the next 10 years or so?

When I was a student the latest technology involved analog synthesizers, magnetic recording tape, and mainframe computers. Music notation with computers was just beginning to be possible, thanks to researchers such as UBC’s Keith Hamel. It is exciting how today’s tools make it easy to compose and record, and even to learn aural skills and music theory concepts. Looking forward, I think we will start hearing music generated by AI that will challenge our notions of musical originality, intellectual property, and artistic value.

“In this technologically mediated and fragmented world, there has never been a greater need for people who can study music deeply and facilitate communication about it.

Music can unite us.”

What advice would you give to someone who is studying to be a theorist? What is it that you wish someone had told you?

In this technologically mediated and fragmented world, there has never been a greater need for people who can study music deeply and facilitate communication about it. Music can unite us. I hope that those who take that calling upon themselves concentrate on music that is enduring and important. There’s little demand for freelance music theorists, though, so this work lives a tenuous existence mostly within institutions of higher learning and needs to constantly connect with the study of performance, history and cultures to remain fresh and relevant. Like most academic disciplines, it can be all-consuming, but it should not get out of balance with your commitments to family, community and spiritual life.

What is one of your most memorable experiences teaching at UBC Music?

In my regular courses that introduced undergraduate to musical form, Baroque counterpoint, harmony, analysis, and post-tonal theory, it was gratifying to see their “ears open,” so to speak; to suddenly hear and understand things they had not consciously recognized before. But my most vivid memories are of when my graduate students brought music to me that I had not listened to closely before, and we would explore it together—blasting the recordings repeatedly—compare our hearings, then find other music like it. Renaissance masses, second Viennese school, Bartók, Liszt, Italian modernists, Bob Dylan, disco, Elliott Carter, spectral music, modern jazz, maritime fiddle music…what a cornucopia of sonic pleasures! What a great job I had. I feel gratitude for the many colleagues and students that have given me this joy.

“What a great job I had. I feel gratitude for the many colleagues and students that have given me this joy.”

Reflections from colleagues and former students

Dr. Leigh VanHandel

Chair, Music Theory Division, UBC School of Music

Although I’ve only been fortunate enough to work with John for a short time, I have admired his research and contributions to the field of music theory for years. As his colleague, I have witnessed firsthand his dedication to his students, his teaching, and to the UBC community.

John is a thoughtful and caring mentor to students and colleagues alike, and he will be truly missed in the theory area and throughout the School of Music.

Dr. Keith Hamel

Chair, Composition Division, UBC School of Music

John and I worked together on some research project in those early years, and I very quickly discovered that no matter how much I thought I knew about a particular topic, John Roeder was equally or better informed, and I was constantly impressed by the breadth and depth of his musical knowledge. This is one of the reasons he was such an excellent supervisor to his graduate students and why we often sought him out to be an external examiner for our graduate students. His insights were razor sharp and his understanding of the complexities of music language was daunting.

John Roeder is a devoted teacher, and probably the most organized and focused person I have ever met. He manages to juggle his teaching, research, supervision, and administrative tasks calmly and effectively, while all the rest of us seem to be scrambling and frantic. His contributions to the School of Music as a teacher, a curriculum developer, researcher, mentor, and administrator are enormous, and his impact on the School of Music will be felt for many years to come.

Dr. Robert Pritchard

Associate Professor, Music Technology

Years later I had the good fortune to team teach music theory with John at various levels. Back then the standard approach to first-year music theory taught rules about harmonic progressions, doubling, and voice leading. John changed that to an approach based on perception, asking questions about what we hear, how we group materials, where is repetition and variation, and so on. For me it was fascinating both for the content and for the student response, and I enthusiastically adopted and supported it. Years later I am very much aware that John’s approach to teaching in his undergraduate and graduate courses continues to influence my teaching in music technology.

John is a model researcher, with his acute and thoughtful observations often appearing in top journals. However, his research results don’t sit in a journal—they find their way into his teaching across different levels, ensuring that students receive new and important knowledge. I recall our third year undergraduates being introduced to beat-class modulations in Reich’s music around the time that John had a paper on that topic published in Music Theory Spectrum, while graduate students were being exposed to John’s work on Torke’s Adjustable Wrench.

In addition to his superlative teaching, John has been hugely instrumental in the administration and development of the School of Music. His experience with committees inside and outside of Arts, his understanding of the politics of the campus, his evaluation of curricula and the ongoing need for updates and expansions, and his thoughtful critiques, timely suggestions, and quiet observations around hirings, funding, building plans, and student recruitment have had an enormous impact on each of us, and we have benefitted from his constant support for the School.

Throughout his time at UBC John displayed his thoughtfulness, caring, acumen, and determination as a teacher, researcher, and administrator. More importantly, he distinguished himself as a genuine, caring person, willing to take on a multiplicity of tasks for the good of others, while maintaining high standards in our chosen art. We shall all miss his insights, his quiet determination, his gentle humour, and his support for many, many students and colleagues across the years.

Dr. Michael Tenzer, Professor, Ethnomusicology

Director, Balinese Gamelan Ensemble, UBC School of Music

This comes naturally only to a few people. With them it appears as ordinary as breathing: it’s just who they are, and that is itself dazzling. They serve as models. They inhabit their beautiful intellectual worlds modestly, never ostentatiously. By pulling much more than their own weight, they offer abundant service to the community and lighten others’ loads. They are always available and timely, always kind, and ready to have an interesting conversation—or a difficult one. They are knowledgeable about many things, offer honest and efficient critique, and will assist anyone who wants to improve what they do. They suffer fools gladly, but when they praise, it really means something. By being themselves, others are given a chance to be better. One is disappointed in oneself when not doing one’s best with them. A desire to emulate their qualities lodges in you and you hope for it to do its work, often in vain.

John Roeder, who retires in spring 2023 after 38 years of teaching at UBC, embodies these qualities more than anyone I have known. He is a musician and theorist who has had a deep impact on his chosen profession. In a scholarly field where the temptation to fly into rootless abstractions can tempt the best, for John—in the words of a referee for his richly deserved Killam Teaching Prize—“the music always comes first—and last”. He has published on a huge range of musical (and other) topics over these years, and could apply his mind to most anything. (I once joked to him that he could write a page-turner theorizing a dust mote.) He is internationally and universally admired by peers. What he can so uncannily do is hear into a music—literally almost any music—and construe explanations for why and how it is the way it is that make your experience richer. You have to do some work to follow him—rewarding work. He elevates not just your musical experience, but your thinking experience, and the way music lends itself to the most elegant and stimulating thought. In this way he enlarges music for those who care to embrace it in new dimensions, making music an even better life companion.

It has been my good fortune to know John well. Aside from all the normal collegial interactions, we co-taught a graduate seminar nine times over the past 18 years. I’m grateful for the education it gave me every time, no matter how many times. I treasure those chances—rare, since professors usually teach on our own—to watch him do what he does. We also co-advised several dissertations so I had the even more revealing opportunity to see how lucidly John line-edits and assesses dissertation chapters. Reading his suggestions, how often did I say to myself “I wish I’d thought of that, but even if I had, I wouldn’t have been able to say it so well.”

Not that many people understand that outside of UBC John is intensely active in his home community and has donned mantles of responsibility that take much of his time each week, every week. It would seem that there are not enough hours in the day for all of this to happen, given how much he puts into being a professor every year, all year. Combined with his university life, that fact elevates his stature still more, since many of us allow our work as professors to consume us to the exclusion of such service.

John, I am sure I speak for all when I wish you the very best and hope that whatever new balance you find will still include us more than a little! We look forward to hosting a symposium in your honour on Saturday June 24 at the School of Music, open to all. The 10 former advisees of yours that were invited to come and present their newest research all jumped at the chance. None would pass up the opportunity to express their gratitude in your presence, and to share that sensation with others who understand what it means to know John Roeder.

Dr. William Benjamin

Professor Emeritus of Music (2014), Music Theory

Former Director, UBC School of Music (1984 – 1991)

The School demonstrated prescience in hiring John, a brilliant young man whose approach to his field seemed at first tangential to some, but turned out to be central. Successive administrators then showed good judgment in doing everything possible to retain him. In return, he made contributions over 38 years that will cause him to be missed as no other colleague has been.

Dr. Robin Attas, M.A., Ph.D., University of British Columbia

In thinking back on my many memories of John, what stands out as a common thread is his ability to truly hear students’ needs and use that as a starting place to guide them towards new discoveries for their benefit rather than his own. When I did my PhD in music theory with John as supervisor, he went along with my creative and occasionally outlandish ideas, yet gently channelled them into outlets that would be recognized as legitimate by others so that I could advance in the field, and shared his knowledge and wisdom with me in a way that still honoured what I brought to the table. A great example of this was his SSHRC grant project on transformational theory, where he worked with me to bring my wild ideas into dialogue with disciplinary ones, and into a publication in a respected journal that was an important stepping stone in my career. I think this is one of John’s great strengths: his ability to see the potential in those around him (whether students or colleagues), and offer his support and guidance to build on that potential, always with a humility that allows him to center the needs of others rather than his own. I’m grateful for the many thoughtful conversations we’ve had over the years, and I wish him all the best with the next phase of his life.

Dr. Tara Boyle, Ph.D., University of British Columbia

I feel so lucky to have been able to work with John Roeder, who brings incredible creativity, rigor, and joy to music analysis in his research and teaching. When I was applying to PhD programs, I was interested in David Lewin’s theory of musical transformations and reading all the scholarship that engaged with its ideas. I was delighted to discover John’s 2009 Music Theory Online article, which renders Lewin’s abstract and mathematical theory tangible by setting excerpts from Bartók to animations of a mouse eating cheese! Needless to say, there is nothing else like it. Soon after that, I realized that John was one of the only music theorists whose work consistently and successfully tackled the contemporary repertoire I loved, and I knew he was the person I wanted to work with. I didn’t even know yet that he was one of our great thinkers on meter, rhythm, and musical time, or of his trailblazing work with Michael Tenzer in the analysis of periodicity and cycle in music across cultures. My time with John at UBC was one of profound intellectual transformation, and I will be forever grateful.

Dr. Gordon Fitzell, Ph.D. (2004), University of British Columbia

I hit the jackpot when John Roeder agreed to serve as my doctoral co-adviser. In fact, I may owe my career to him. As I quickly learned, he is as kind and supportive as he is brilliant and creative. It is very easy to sing his praises, but here’s one quiet story that speaks to all these qualities.

John wrote a reference letter for me when I was applying for a position at the University of Manitoba, an institution where I have now taught for the past 19 years. I still recall that when the chair of the hiring committee offered me the job, he noted, in almost bewildered admiration, John’s deeply thoughtful, meticulously crafted, and comprehensive five-page letter. “Five pages!” I recall him exclaiming. (The chair was far more animated about John’s letter than my hiring.) I am very grateful to John for supporting me in this way, but I suspect this is the sort of noble deed that he carried out regularly—a day in the life of being John Roeder. I once attempted to express my gratitude to John, but he wasn’t having any of it.

Kristi Hardman, M.A., University of British Columbia

John and his research with Michael Tenzer were huge influences on my research interests and he continues to be an influence on my work to this day. I had always been interested in music outside of the Western canon including rhythm and meter, but I didn’t know that people studied these until I was sitting in John and Michael’s Periodicity classroom. Some of my fondest memories from my university studies come from being in that class and working closely with John and Michael on their research of cycles. John was always extremely interested in discussing any type of music, and willing to consider different ways of hearing music that were presented to him by his students. I will never forget John waiting for me at the end of the convocation stage to give me a hug after receiving my degree from UBC; I think that sums up his care for his students. He will surely be missed at UBC.

Dr. Eshantha Peiris, Ph.D., University of British Columbia

At a time when music theorists and ethnomusicologists can seem to occupy different worlds, John Roeder’s recent research serves as an exemplar of how thoughtful analyses of a variety of global musics can shed light on cultural idiosyncrasies as well as on broadly shared musical perceptions. As a student of ethnomusicology, I was fortunate to have Prof. Roeder as a mentor, through the “Cycles in the World of Music” research group at UBC and as a member of my dissertation committee; I am grateful for the sense of direction that I received from his incisive feedback and encouraging attitude. He inspired his students not only through his rigorous scholarship but also through his kindness and concern for others; I hope that this sense of humanity will become a part of his legacy that is carried forward by the next generation of music scholars.

By Dina MacDougall

Marketing & Communications Strategist