In the 1980s, Vancouver was a rock ’n’ roll mecca. High Notes talks to Prof. Nathan Hesselink and Sharman King (BMus’70) about the UBC alumni who made some of the era’s best and boldest albums possible

Prof. Nathan Hesselink and Sharman King

Here’s a little-known fact: Vancouver is the birthplace of some of the most important rock ’n’ roll records of the past 40 years. Beginning in the late 1970s and continuing through the 1990s, acts like Van Halen, Aerosmith, Bon Jovi, Metallica, Blue Öyster Cult, INXS, and the Scorpions flocked to the city to record their iconic albums.

Even less known is the role the School of Music played in the city’s transformation from local hub to international hard rock mecca. That is, until recently: Prof. Nathan Hesselink stumbled upon this secret history while doing research for a project on rhythm and technology in rock music.

PLAYLIST: Little Mountain Sound

Listen to some of the iconic songs recorded in Vancouver during the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s

“I was talking to local sound engineers and producers and UBC kept coming up. As it turned out, our alumni had their fingerprints all over these great albums from that era,” he told High Notes recently.

Encouraged by fellow faculty member Sharman King (BMus’70) — whose long and successful career as a bass trombonist included a stint as a studio musician at Vancouver’s legendary Little Mountain Sound Studios — Prof. Hesselink tracked down and interviewed as many producers, composers, musicians, and engineers from back in the day as he could find. He pored through archives that hadn’t been opened in decades. His detective work took him on a journey back in time, from the heyday of the 1980s, to the launch of the Bachelor of Music program in the early 1960s, all the way back to Vancouver’s first jazz supper clubs and CBC Radio’s early experiments with live music broadcasts. His research culminated in an eye-opening talk at the School of Music this past February.

High Notes sat down with Prof. Hesselink and Sharman King to discuss the project so far.

For starters, can you describe the scene at its peak?

Think about the big albums of the ‘80s and there’s a good chance they were produced in Vancouver: Bon Jovi’s Slippery When Wet, Aerosmith’s Pump, Van Halen’s Balance.

— Prof. Nathan Hesselink

Nathan Hesselink: It’s no exaggeration to say that Vancouver was a rock ’n’ roll mecca in the 1980s and 90s. Think about the really big albums of the ‘80s and there’s a good chance they were produced at Little Mountain Sound: Bon Jovi’s Slippery When Wet, Aerosmith’s Pump, Van Halen’s Balance. Bold, important albums that sold tens of millions of copies internationally and came to define the hard rock sound of that era. The biggest bands in the world were coming to Little Mountain Sound Studios to record their music. Metallica, AC/DC, The Cult… pop acts like Bryan Adams and INXS, too. The list goes on and on.

What attracted these bands to Vancouver?

Nathan Hesselink: It was a combination of first-rate recording facilities and abundant local talent. Two UBC grads, Brian Griffiths (BMus’65) and Brian Gibson (BMus’64), had launched Little Mountain Sound in the early 1970s. It was one of the largest and most technologically sophisticated studios in all of Western Canada. Little Mountain was the first studio in Vancouver to have a 32-track recorder, which was a big deal back at the time.

But the talent was the real draw. A generation of young musicians, producers, engineers, arrangers, composers, and songwriters was coming into its own around then. Many were UBC grads: engineer-producer Bruce Fairbairn (BSc’70, MSc’74), songwriter Jim Vallance (a UBC piano major from 1970-71), composer Peter Berring (BMus’77), musicians like Tom Keenlyside (BMus’76) and Claire Lawrence (BMus’67), and CBC producer George Laverock (BMus’66), to name a few.

At the centre of it all was Fairbairn, who, along with Bob Rock and Mike Fraser, would form the production power trio at Little Mountain Sound. It was those three who produced the albums that most people will be familiar with. Fairbairn studied biology and environmental science at UBC but spent much of his time in the orbit of the School of Music. He was a talented trumpet player and with friends from the UBC School of Music started the jazz-rock band Sunshyne and later helped launch the prog-rock band Prism.

But it was Fairbairn’s work as a producer with Loverboy that put Vancouver on the international map. This was around 1979 or 80. He produced Loverboy’s first album, which went double-platinum in the U.S. — it sold over a million copies in Canada alone. The sudden success of this unknown Canadian band turned heads south of the border. Soon, big name acts were coming north to work with Fairbairn and the incredible roster of talent at Little Mountain Sound.

LISTEN: “Working for the Weekend” by Loverboy. UBC alumnus Bruce Fairbairn produced their debut album

Much of this talent came from the UBC School of Music. Why?

Sharman King: There was a real renaissance happening at the Department of Music (as it was known back then) beginning in the early sixties. The BMus degree was launched in 1959 and soon after UBC recruited some very talented faculty, people like Dave Robbins and Cortland Hultberg. Dave Robbins was a big-time American musician. He was an exemplary trombone player and a very good leader. He was very skilled at writing and promoting music. Cortland Hultberg was this young, dynamic music theory teacher and a talented composer in his own right. The two of them launched many, many careers over the next 20 or 30 years. People like Jim Vallance, Brian Gibson, Brian Griffiths — they all studied under Hultberg and Robbins and really benefitted from the influx of new ideas and skills those two brought with them.

Technology was changing too. Our famous alumni from back then, you can see how in the late 1960s and especially the 70s they blundered into careers that didn’t exist five years before, but now existed because of technology and the changes in musical style that it brought. Technology allowed us to play faster and with different beats. And a lot of this technology was developed at and exported from UBC! For example, Ralph Dyck and Wayne Carr were making early solid state amplifiers in the sound booth at the School of Music.

You never know as an undergrad what’s going to become of your studies, but that booth was really important for many careers. That’s were I learned that I liked recording and therefore liked being a recording musician. That’s where Don Harder (BMus’78) got started. He had a distinguished career at CBC and as a freelance recording engineer and has a few Grammy awards under his belt.

And as you have both pointed out, Vancouver was an important musical destination long before the rock ’n’ roll era.

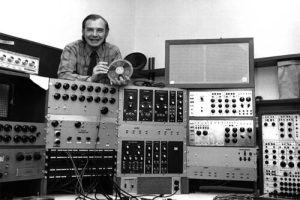

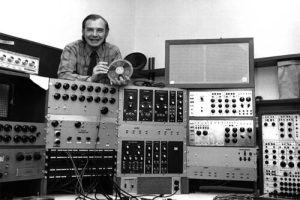

UBC Prof. Cortland Hultberg. Photo: UBC Archives

Sharman King: That’s right, you could go all the way back to the mid-1930s when the CBC was formed as part of a national unity effort. Live music was an important part of their broadcasts from the very beginning, which created demand for talented professional musicians in Canada’s big cities. One of the results of this was that musicians had to be very good because there are no second takes on live radio. The musicians had to be very sure of their timing. So the skills were developed way back then. And as Nathan’s research shows, the music scene in Vancouver really got going after WWII, when there was a market for various kinds of music that were recorded and promoted. This gave rise to the downtown jazz scene, with excellent supper clubs like The Cave, which were still going strong well into the 1960s and 70s, to the establishment of Aragon, the first recording studio in Vancouver, which was originally country and western.

Nathan Hesselink: By the 1950s Vancouver had all the components necessary for a music industry: good musicians, good writers, decent studios, and the knowledge to put it all together. UBC was a pipeline for new talent, and thanks to people like Hultberg, found a niche for itself promulgating new music production methods. In addition, of course, to training many excellent classical musicians, as it still does.

The pace of technological change really picks up in the sixties and seventies. What impact does that have?

Sharman King: The technology and the music were always chasing each other. The early four track recording was at Aragon (later Mushroom) in 1968 but it was just a matter of a few years until UBC music grads Brian Gibson and Brian Griffiths’ production house brought Geoff and Jean Turner to design, build and run Little Mountain Sound in 1972. When the first 16-track recorder arrived in Vancouver, boy did that give us new flexibility. With the brass sound, it became possible to double- and triple-track stuff. You could record fairly simple horn lines, then stack each track until it got this buzz to it, which was something you couldn’t easily do before. Same with strings — you’d hire eight strings and stack them, stack them, stack them, until it sounded quite ginormous, more like a string section than eight players.

Nathan Hesselink: Technology changed what was possible, the music adapted to that possibility, and that pushed the technology further in turn. So it really is this confluence of technology and talent in the sixties and seventies that makes what was happening in Vancouver in the 1980s possible.

WATCH: “Livin’ On A Prayer” by Bon Jovi. Their multi-platinum Slippery When Wet album was recorded at Little Mountain Sound Studios in Vancouver

Is there a distinctive ‘Vancouver’ sound to those big albums of the eighties and early nineties?

Nathan Hesselink: There’s more horn playing on those classic hard rock albums than people realize. A lot of those Aerosmith albums have quite a lot of brass on them. It’s subtle, coming in at the end of a second verse or chorus, but it’s there. The presence of brass on these albums had a large part to do with the local scene but particularly Bruce Fairbairn, who loved to have brass arrangements. Even on later Yes albums. You still have brass in the texture.

There was a kind of sophistication to Fairbairn’s arrangements, and he brought in a lot of acoustic players, mostly brass, but also strings sections. I’m still trying to trace exactly Fairbairn’s influence, he was on so many albums, I can’t automatically identify the albums he produced but some of the studio musicians from that era definitely could. Very subtle things, in terms of the arrangements, so that when you get to the second or third verse, always some little thing has changed or been added, that’s one reason for the longevity of those songs, I’m sure — subconsciously listeners probably hear that.

What’s next for your project?

Nathan Hesselink: My goal is to publish my research in the next year to eighteen months. The response to the talk was great and I think it’s important that more people know about Vancouver’s — and UBC’s — rock ’n’ roll legacy.

In the latest Playlist column, Prof. Hesselink and Sharman King share highlights from Vancouver’s heyday as a pop and rock mecca. Listen here.

Banner image: Prism in concert (Wikimedia Commons)