Dr. Jonathan Girard and the UBC Symphony Orchestra shine a light on century-old symphonic treasures by the Jewish-Hungarian composer

By Tze Liew

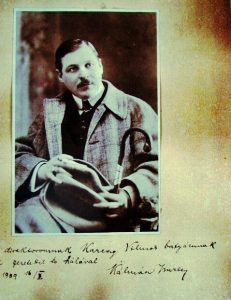

Composer Emmerich Kálmán

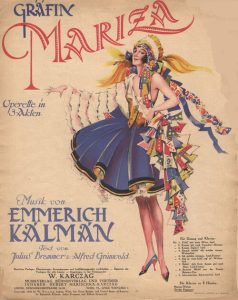

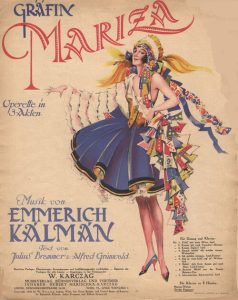

Emmerich Kálmán couldn’t sing, and wouldn’t dance — but his music has moved hundreds of thousands of operetta-goers to fits of tears and waltzes of joy. Capturing many a heart with gems like Die Csárdásfürstin (The Gypsy Princess) and Gräfin Mariza (Countess Maritza), Kálmán is a glittering beacon among names like Johann Strauss and Franz Lehár, and currently the most performed operetta composer in the world.

What most of his fans probably don’t know is that, early in his career, Kálmán (1882–1953) wrote orchestral works in the vein of Liszt and Bartók. These include two rarely-performed manuscripts, one of which was stowed away in a drawer for almost a century, never to see the light of day — until now.

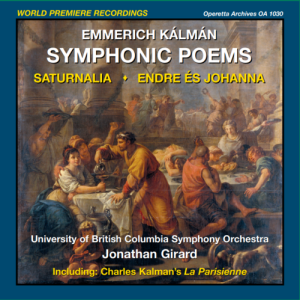

“He started out, as most operetta composers seem to do, with ambitions to become a ‘serious’ classical composer.”

The UBC Symphony Orchestra, under the baton of Dr. Jonathan Girard, recently released Emmerich Kálmán — Symphonic Poems on the Operetta Archives label, featuring world première recordings of Kálmán’s two early symphonic poems, Saturnalia (1904) and Endre és Johanna (1906). Written before Kálmán embarked on his journey as an operetta composer, they are fascinating pieces: Saturnalia brings to life the traditional wild revelries in honour of the Roman god Saturn. Endre és Johanna is inspired by the 1885 novel by Hungarian writer and politician Jenő Rákosi, depicting the tragic 14th-century marriage between Johanna, granddaughter of King Robert the Wise of Naples, and her cousin Andrew, son of King Charles I of Hungary — when she was five and he six.

WATCH: An excerpt of Endre és Johanna premièred by the UBC Symphony Orchestra

To discover symphonic poems by a major composer is like finding shipwrecked treasure — and Girard is passionate about bringing light to obscure works. He had always known of Kálmán, but his interest was further piqued while conducting with the Ohio Light Opera, where at least one Kálmán operetta was put on every other summer. There Girard met Michael Miller, a long-time Kálmán crusader, friend of the Kálmán family, and head of the Operetta Foundation, who told him about the tone poems that had never been recorded commercially.

“Emmerich Kálmán was born in Hungary and studied at the Music Academy in Budapest, with Zoltán Kodály and Béla Bartók as fellow classmates,” says Miller. “He started out, as most operetta composers seem to do, with ambitions to become a ‘serious’ classical composer. He’d originally also wanted to become a concert pianist, but couldn’t because of a nerve injury to his hand. Saturnalia and Endre és Johanna were two very serious works that he wrote while studying in Budapest.”

Kálmán’s tone poems were generally well-received in concert. But to his great frustration, he was unable to secure a publisher for these pieces. Soon after, he wrote a handful of humorous cabaret songs, which did get published and were all the rage in Budapest — but still no such luck with his symphonic pieces.

“Kálmán half-jokingly told his friends that if this got any worse, he would have to write an operetta,” says Miller. “And so he did. He wrote his first operetta, Tatárjárás, in 1908, fusing Hungarian musical elements with Viennese waltz stylings, and it was a huge hit in Budapest. He was brought to Vienna by operetta composer Leo Fall and some famous theatre impresarios, and that put Kálmán on the operetta map.”

Kálmán was so popular in Germany that he became one of Hitler’s favourite composers — despite his Jewish origins.

Emmerich Kálmán as a young man in 1909, the year of his “Herbstmanöver” success.

In 1909, Tatárjárás premiered in Vienna under the title Ein Herbstmanöver (An Autumn Maneuver), and was an immediate sensation — spreading like wildfire to Broadway and hundreds of theatre capitals including Moscow, Sydney, Stockholm and Buenos Aires. In 1915, he bedazzled the world with Die Csárdásfürstin (The Gypsy Princess), his most successful operetta to date, with a record — just in its first quarter-century — of over 100,000 performances worldwide and more than 30 translations. The years 1915-1930 marked his most prolific years, producing eight wildly popular operettas brimming with joie de vivre that further propelled his fame.

Kálmán was so popular in Germany that he became one of Hitler’s favourite composers — despite his Jewish origins. The story goes that Hitler offered him the status of an ‘honorary Aryan,’ but Kálmán refused, fleeing to Paris after the Anschluss. He emigrated with his family to the United States in 1940 and eventually became an American citizen.

“What we start to see in Kálmán’s music — beginning in the early 1920s — is the inclusion of popular jazz idioms and dances, from the shimmy to the foxtrot to the blues,” says Girard.

Sheet music cover of Gräfin Mariza, 1924

Ever adaptive to his cultural surroundings, Kálmán continued to appeal to the mainstream with operettas whirling with sound and colour. After the war he was encouraged by his fans and publishers to return to Europe in 1949. He passed away from a heart ailment in Paris in 1953, leaving behind a legacy of twenty engaging operettas, with subjects ranging from circus princesses to Arizonan racehorses.

“Kálmán had a real talent for incorporating popular cultural elements around him into his music. He had very few failures on the stage — almost everything he wrote was a big success, which is rare for most composers,” says Girard. “But as a result of his operetta fame, his early symphonic works were just ignored for a long time.”

Girard and Miller began to toss around the idea of reviving Kálmán’s symphonic works in performance and in recording. Miller contacted Kálman’s son in Munich — Charles Kálmán, also a composer, who had kept his father’s Endre és Johanna manuscript safe in a drawer for decades. Saturnalia, although rarely performed in recent times, had been published and was readily accessible.

“Endre és Johanna didn’t actually exist in a performing edition, so I had to create an edition that could be played by an orchestra,” explains Girard. “I also wanted to make it as user-friendly as possible, so that future orchestras can hit the ground running with it. This involved creating a set of parts, editing and fixing discrepancies in the score. Kálmán marked the score both in German and Hungarian, so there was translation work to do. And his handwriting was not clear, so it was an interesting exercise to try to figure out what he wanted in the score at points.”

Given the 23-minute length of the work, it was no small feat for Girard. As the editor he sought to fully preserve Kálmán’s musical intentions, but this was not always easy with incomplete information.

“Sometimes there were chords and accidentals missing, or an inconsistency in articulation and dynamic markings. As the editor you have to make precise judgment calls on what you think the goals were. You don’t want to colour the composer’s intentions, but at the same time, you’re helping put forth the work in the best possible light.”

Beyond creating the orchestral score, getting a student orchestra to perform the works posed another unique challenge. The UBC Symphony Orchestra often premieres works by contemporary composers, but interpreting and premiering works from a hundred years ago, with no living composer to guide the process, is a different story.

Clues lie in Kálmán’s operetta music instead. He understood the voice and wrote in a very lyrical manner — a quality that can be found in his symphonic poems, which seem a world away from his operetta music at first glance.

“A lot of scholars have talked about the alternating moods that Kálmán evokes in his operettas. You literally go from tears to laughter, ecstasy to melancholy. For instance, the overture to Ein Herbstmanöver opens with military grandeur, the sound of cannon fire and whinnying horses. Then after that you hear this most beautiful, intimate little waltz. It’s this juxtaposition of emotional states that makes his music so satisfying to play and to listen to,” says Girard. “These characteristics exist in his symphonic poems: we have moments of grand orchestration with the whole orchestra playing at full volume; and then a very intimate chamber music experience at another point.”

“His fame as an operetta composer has actually diverted attention away from these fine tone poems. But all of his music has a fundamental human quality that touches us all.”

— Dr. Jonathan Girard

“Dr. Girard would tell the orchestra that whatever else was going on in our life, we could leave all of that at the stage door and create music together with a unity of purpose,” says Billie Smith, concertmaster for several of the premieres and Girard’s post-production assistant. “He provoked us to communicate through energy and physicality, which is a necessity for playing these pieces which have so much tension and mercurial emotional extremes.”

In October 2013, the UBC Symphony Orchestra — with the goal of ultimately producing a commercial recording — presented the North American premiere of Saturnalia. In March 2016, they performed and recorded Endre és Johanna, the overture to Ein Herbstmanöver, La Parisienne by Charles Kálmán, and two operetta arias: “Fein könnt’ auf der Welt es sein” from Gräfin Mariza with tenor Scott Rumble (MMus’18), and “Heia, heia, in den Bergen ist mein Heimatland” from Die Csárdásfürstin with soprano Elana Razlog (DMPS’16, MMus’17) and the UBC Opera Ensemble.

“La Parisienne is a really charming little waltz for orchestra. Charles was also interested in popular music — you can hear shades of Chabrier, Ravel, Khachaturian and also Hollywood in the piece,” says Girard. “I thought it would be really interesting to include a father and son on the same CD, to showcase this vertical sampling of Kálmán.” Sadly, Charles Kálmán passed away on February 22, 2015 before he could witness the fruition of the CD.

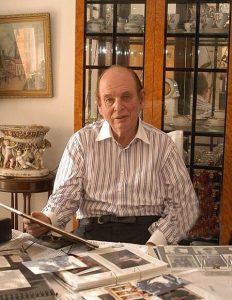

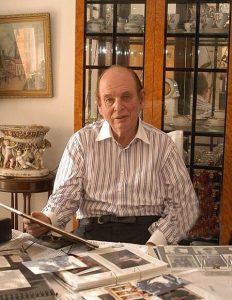

Charles Kálmán

“”Fein könnt’ auf der Welt es sein” is sung by the character Tassilo, who laments how men don’t understand women and that they bring them many burdens, but at the same time men need them and things wouldn’t be the same without them,” says tenor Scott Rumble. It is a beautiful aria that, bafflingly, is often cut from productions of the operetta.

“Heia, heia” is the iconic opening to Die Csárdásfürstin, where a Magyar maiden in a Budapest nightclub sings of her mountainous homeland and her search for a partner to equal her own fiery passion.

“It was a real pleasure to work with such talented singers as Scott and Elana. And Nancy Hermiston did a great job directing the students in the UBC Opera Ensemble — they pulled off a really rousing chorus. I think it was a great triumph for the school to be able to bring together the orchestra and opera ensemble to explore this music,” says Girard. “There aren’t many places that are able to do this, and I think we’re really unique here in the breadth of repertoire and quality of what can be performed.”

The whole project took seven years to complete — culminating with the official CD release in October 2020. It was truly a labour of love.

“The Kálmán pieces have stayed with me since we recorded them. I felt like we achieved a truly magical connection to these pieces, taking a range of human experience and elevating that into a greater shared consciousness,” reflects Smith.

The CD is now available for purchase on the Operetta Foundation website and through select online and retail outlets. This month, it received its first major broadcast on Bavarian Radio in Germany. Girard and Miller are working hard to garner more attention for the CD from media and broadcasters, and get it distributed to major university library archives.

Like many composers who are critical of themselves, Kálmán himself had been disparaging of his early works — looking back he had even called Endre és Johanna a “real, old, crappy cavalry boot.”

“These works are nonetheless musically engaging, important because of their rarity, and provide a critical puzzle piece in helping us understand his evolution as an operetta composer,” says Miller.

Recently, Girard’s work in creating the orchestral score has been generating interest from other university orchestras — the hope is that Kálmán’s symphonic pieces will continue to be performed and live and breathe as part of his canon.

“It’s been fascinating to see the breadth of what Kálmán was able to produce,” says Girard. “His fame as an operetta composer has actually diverted attention away from these fine tone poems. But all of his music has a fundamental human quality that touches us all.”