Professor of Cello Eric Wilson teams up with Dené leaders and UBC academics on a cross-cultural multimedia project honouring First Nations music and activism

By Tze Liew

From a grassy ring in an outdoor pavilion, the sound of Dené drumming rings out to the mountains and rivers of the Mackenzie Valley: proud and vigorous, the pulse of a galloping heartbeat. Accompanying this is the sonorous voice of Dené leader Angus Ekenale, his eyes closed in fervour as he leads a traditional song while pounding on a hand drum. His voice is filled with colours: sometimes quavering, sometimes a chested cry, and then a low hum, inviting more and more voices from the Liidlii Kue First Nation to join in as one chorus, one spirit.

Perched on a cliff overlooking a torrential river, Professor of Cello Eric Wilson draws out the first notes of a sweeping, majestic melody on his cello. It sounds like the heartstrings of nature — music that sets free the spirit of raging rivers, vast blue skies and sprawling rosy sunsets. A tribute to the Mackenzie River Valley, and the First Nations guardians who have kept it pristine and welcoming.

The interweaving of these two musical cultures is at the heart of the Dehcho project — a multimedia collaboration celebrating the music and history of the Northwest Territories, and a bridge for reconciliation between Indigenous communities from the North and non-Indigenous people from the South. Spearheaded by Chief Gerald Antoine, leader of the Liidlii Kue First Nation, and a team of artists and educators, including UBC faculty and alumni, the project launched in 2015 with the ancient drum dances of the Dené people and has grown to include Dené hand games, Gwich’in fiddling and Inuvialuit drumming.

“The project traces its roots back to the Berger Inquiry in 1975 that halted the construction of a massive pipeline project running through the Yukon and the Mackenzie River Valley.”

Prof. Wilson travelled through the Valley as part of the project team, learning about Dené culture, filming their traditional songs, and sharing cello music with the communities in return. “We were first invited by Chief Antoine to meet drummers from the Liidlii Kue First Nation. When you are in that fortunate situation, you go humbly, you are a guest,” he says.

The project traces its roots back to the Berger Inquiry in 1975 — a key undertaking led by Justice Thomas Berger from the Supreme Court of B.C., that halted the construction of a massive pipeline project running through the Yukon and the Mackenzie River Valley. Justice Berger and UBC Law Professor Michael Jackson, who was acting as Special Counsel, travelled to thirty communities across the north to help Dené and Inuvialuit leaders plan the hearings, where they demanded that their land claims be settled. The testimony and many of the drum dances that celebrated the visit of the Inquiry were recorded on tape.

These tapes resurfaced ten years ago, when Prof. Jackson asked Daniel Séguin, a Gemini and Leo-awards winning composer with a strong interest in social justice projects, to digitize them for a modern audience. “Michael Jackson hoped that, with Seguin’s help, those recordings could be digitized and returned to the northern communities,” says Drew Ann Wake (BA’76, MA’84), a curator and key player in the Dehcho project, and who had attended the Inquiry as a young CBC reporter.

Chief Gerald Antoine, leader of the Liidlii Kue First Nation, spearheaded the Dehcho Project in 2015

The first digital masters — of drumming recorded 40 years ago — were presented to Chief Antoine in Fort Simpson. “There are messages and stories that go with the songs,” Chief Antoine says. Recognizing the spiritual need for young Dené people to inherit the old songs, he set the terms of partnership for the Dehcho project: Drew Ann Wake would pay to fly Dené elder and drum dance master Angus Ekenale from his home in Wrigley to Fort Simpson, and UBC Studios would send videographer Christopher Aitken to film him performing ancient songs. Both the Dené people and the project team would be able to use the videos for educational and archival purposes.

Around this time, Séguin had the idea to create a musical work that would be a river journey — pairing traditional northern drumming with a companion cello piece that Wilson could perform. It would be a way for the two cultures to speak to each other.

“I thought that maybe after all these centuries we could come together through our music,” says Séguin. “Maybe we could share with the Dené, instead of taking from them.”

Séguin and Wilson began to work with Wake, who was curating Thunder in Our Voices — a UBC-sponsored traveling exhibition that showcased northern Indigenous artwork inspired by recordings from the Berger Inquiry. The art, paired with a photo montage and historical speeches, was set to Séguin’s cello piece, Dehcho (which means “big river,” referring to the great Mackenzie).

“We thought the cello, which is so close to the human voice, would be fitting as a metaphor for the voice of humanity,” says Wilson. “It also represents the traveller, one who is invited into First Nations land to experience it.”

In 2017, the Dehcho project won a Canada Council New Chapter grant as part of the 150th anniversary of Canada. That summer, Wilson, Séguin and their team embarked on their river journey — up north to Fort Simpson to share music with the Liidlii Kue First Nation drummers.

“We were like tiny ants travelling in a giant leaf, trying to find our way among the veins. Fortunately our guide, an elder, knew the territory like the back of his hand,” Wilson recalls. “It was very sparsely populated, vast, and overwhelmingly beautiful.”

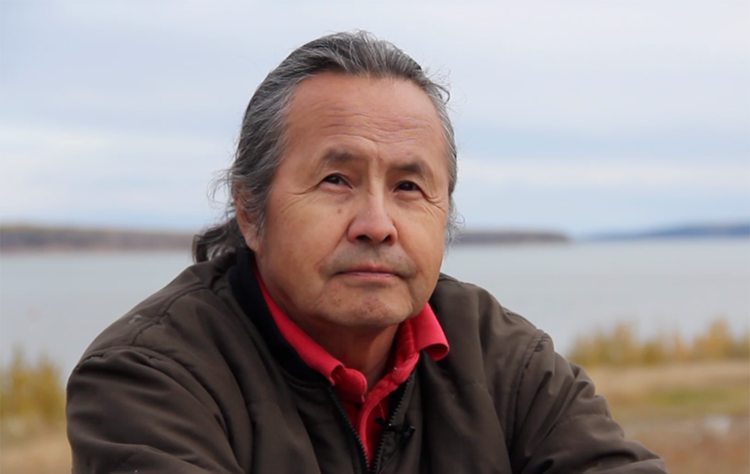

Drum dance master Angus Ekenale

At Fort Simpson, Chief Antoine and Elder Ekenale taught them about drum dances, and how the millenia-old art form is woven into the fabric of the lives of the Dené community.

“De makes reference to the river, and né to the land. The Dené people evolved from the essence of land and river, which are tied to our creation and survival,” explains Chief Antoine. “We celebrate this sacred connection, through song and drums, in prayers and ceremonies.”

The drums themselves are the voice of the land: hide made of caribou belly skin, wood made of birch, and fastenings made of babiche (sinew). Carrying the heartbeat of the land and Creator, the drums ring out at all kinds of special occasions — weddings, funerals, births, harvests, meetings, spiritual healings and more.

“Elder Angus Ekenale told me how he uses song and drumming to move his people in expressions of joy or solemnity, according to the occasion or ceremony,” says Wilson. “I can only imagine how many stories he has expressed through his music, just as I have over the decades that I have lived in music.”

Wilson and Séguin saw a drum dance live for the first time at the Hand Games: a traditional Dené sporting event. Originally designed as physical and mental tests to develop hunting and fishing skills, the hand games are not unlike what a major football game is to the southerners — people gather with excitement from far and wide.

“When I heard the drums played live for the first time, I was mesmerized,” says Wilson. “The drums and the voices together, that is the heartbeat of a nation. Then, watching the people of the Liidlii Kue First Nation dancing in a circle, you realize: this is not a ritual, it is a profound community experience.”

“’De’ makes reference to the river, and ‘né’ to the land. The Dené people evolved from the essence of land and river, which are tied to our creation and survival. We celebrate this sacred connection, through song and drums, in prayers and ceremonies.”

— Chief Gerald Antoine

It was only fitting that this gift of community music would be reciprocated during Canada 150, through the voice of Dehcho. At the end of their visit, the project team presented their multimedia exhibition at the Open Sky Gallery to a packed audience. The front row was reserved for a group of women Dené elders. As Wilson began to play, with a video of the grand northern landscape projecting behind him, the women put their hands over their hearts, feeling the vibrations of the cello reverberating inside them. “Dehcho weaves together two different musical traditions that share the same emotional intensity,” says Martina Norwegian, Director of the Fort Simpson Historical Society. “They have a deep connection…if you listen for it.”

“They were all looking at each other with this look of joy on their faces, physically feeling Eric’s music,” says Drew Ann Wake. “And I thought, Oh, this is a once in a lifetime experience for me. It was beautiful.”

In the evening, the team headed out to film Eric playing Dehcho on the riverbank. “It had been raining all afternoon, but minutes before we started filming, the sunset appeared, flooding the clouds and the river below in a flush of pink and orange. Eric playing the cello over that golden river, with mosquitoes flying in bunches around his head will always be the perfect piece of music to me,” laughs Wake. The footage has now been edited into a video showcasing the Liidlii Kue Drummers, and background orchestral music performed by the UBC Chamber Strings.

Since then, the Indigenous elders and the project team have brought the project to many more communities. It continues to grow and take new forms. In September 2019 the team filmed Gwich’in fiddler Michael Francis on the grassy banks of the Mackenzie Delta. They gave a performance to a packed school gym in Tuktoyaktuk. They drove to the village of Tsiigehtchic, where Eric gave a music lesson at the local school that encouraged each student to take a turn with the cello.

Most recently, during the summer months of COVID-19, the project team has been working to incorporate these recordings of Wilson and the Indigenous musicians into online curriculum packages, to be used by schools across the North. The materials will also be put on the Indigenous Foundations website at UBC. They hope to get Indigenous youth excited about their own music and legacy.

Looking forward, the team hopes to embark on another boat journey from Fort Simpson to the Delta next summer. Wilson also anticipates plans for Chief Antoine to visit the UBC School of Music for a roundtable discussion on traditional drumming, whenever COVID restrictions have been lifted. This is a precious exchange that Wilson hopes will continue into the future — a spirit of mutual curiosity, respect and understanding that transcends cultures and borders.

“To think, after all that has happened in the past, all we have taken from the north, people still welcomed us as outsiders who had something to share,” says Séguin.

“Music is a conduit for all people,” says Chief Antoine. “It creates the possibility for us to connect, to recognize each other and where we come from. To understand what our lands and rivers mean to us, and to ensure a good life for our children, grandchildren and those yet to come.”