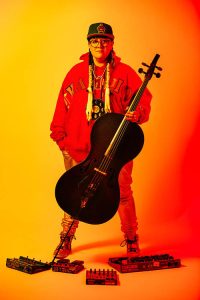

Award-winning cellist Cris Derksen (BMus’07) on the urgency of Indigenous activism in the arts, the importance of hustle, and the future of live music in a post-pandemic world

Cris Derksen (BMus’07) has made a career out of blurring the boundaries between genres. Photo: Tanja-Tiziana

Cris Derksen is home. The COVID pandemic has brought the Juno-nominated cellist’s life on the road — more than a decade of near constant-travel, with frequent stops on the folk, classical, art and fashion circuits in Canada and abroad — to a sudden halt. Yet she finds herself busier than ever.

Since the lockdown began, last March, Derksen has composed music for the Calgary Philharmonic Orchestra, collaborated on an “art-dance-fashion” film for Indigenous Fashion Week Toronto, scored a documentary series for the Knowledge Network, and performed many virtual concerts, including a Wednesday Noon Hours event for the School of Music.

“It’s been kind of a lovely treat to be at home for ten months,” she says.

Derksen credits her success during this difficult time to a determined, pan-genre approach to music that dates back to her days as a UBC music student, and to her experiences as a Two-Spirit person of Cree and Mennonite descent in Canada’s white, settler-dominated music industry. It’s an approach that has ultimately served her well as an artist and as someone immersed, out of necessity, in the business of music.

In November, Derksen spoke with the School of Music’s Prof. T. Patrick Carrabré about the urgency of Indigenous activism in the arts, the importance of hustle, and the future of live music in a post-pandemic world.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity. Watch the full conversation here.

How have you been managing during all this lockdown? I see you active on social media and doing lots of concerts, but tell us what life is like.

Derksen: You know, I hadn’t been home since I graduated from UBC, really. For thirteen years, I’ve been on the road. And it’s been kind of a lovely treat to be home. I’m even busier than I imagined. I’m doing performances, I’ve done some classical commissions, a choral commission. I just finished Indigenous Fashion Week Toronto — 40 minutes of straight art, dance, fashion, and film, all combined. I was the lead composer for that. Now I’m going straight into a four-part docuseries that is due at the end of January for Knowledge Network. It’s called B.C.: A History, and it covers first contact between Indigenous peoples and European settlers, and explores how white settler governments passed laws to make it easier for white people to get ahead and definitely made it hard for any folks of colour to maintain any sort of liveable situation. So that’s what I’m diving deep into. As well as these online concerts that I record at night [laughs].

I think that’s interesting, because you really do balance the performing and the creative side of things, which I’m sure keeps you very flexible. You were a performance major at UBC, and from that you’ve developed this really varied career. Can you give us an idea of how that evolved?

Derksen: I arrived at UBC as a string player with a little bit of a different perception at the beginning. I knew I didn’t want to play at a desk in an orchestra. I wanted to be a really good player so I could play my own music. So I went to UBC with the idea that I was there to learn the skills and discipline you need to maintain a rigorous working life. Skills I could take from UBC into the real world. But I also wanted to do things my own way.

I was super-fortunate that I was already touring with Tanya Tagaq before I graduated, in 2007. So I did my grad recital, and the next day I went to perform at the Glenn Gould Studio in Toronto, and the day after that we went to Spain to perform for WOMEX. It was just like the path was already set out. And again it goes back to me wanting to do something different — I was creating that path while I was at UBC. I had a clear vision of what I wanted to do.

Another thing that really helped was Dr. Sal Ferreras’s music business course. I took a lot arts business courses that taught me how to get grants.

What kind of skills would you recommend students think about as they prepare to go out into the professional world?

Derksen: I think trying to be as diverse, as multidisciplinary as possible. Like, if you’re a composer, work with as many mediums as you can: animation, dance, theatre. Even in the visual arts world, there’s a lot of room for music. Movement and dance and music, it’s all one thing, in a way. So it’s about getting your name out there and doing as many different projects as you can get your little hands on. But I also would really recommend creating your own projects, creating your own work. Going for those grants that allow you to develop what you want to do. One, these projects can give you an income to live off of. Two, they can help you see where you want to be in the future.

So did you start applying for grants early on?

Derksen: I think I got my first grant three years after graduating. But I definitely applied for grants before that. For students right now, the Canada Council has a huge mandate to fund new and emerging artists and first-time applicants, so it’s a really excellent time to apply. I sit on these grants boards, and I see kids coming straight out of universities, starting their own new music collectives, and they’re being quite successful. I’m all for it.

As a matter a fact, I think the last time you and I saw each other, we were sitting on one of those panels [laughs]. You’re right. Grant-writing really becomes a part of the life of the independent artist — learning to articulate what we want do in such a way that it’s clear what we need the money for.

Derksen: Exactly, and by writing the grant, you’re not just making your project clear for the jury. At the same time, you’re making it clear for yourself. I actually start with the budget. I’m like, “How much do I need to do what I want to do? What are my dreams?” Dream big, aim high. Not too high — be realistic!

That’s incredible advice. So you as an artist, when you apply for grants, how do you articulate your positionality? You come from a classical tradition but you have Indigenous heritage, you’ve worked with pop groups and done film work — how do you articulate that positionality?

Derksen: Right. My perception is quite unique. I’m Indigenous, I’m half-Cree, half-Mennonite. I come from a classical background. I work with electronic tools. I’m really into creating music that is accessible and relatable. I’m into bringing classical music into a space that folks who don’t usually go into classical spaces can feel comfortable with.

Because I’m pan-genre, I fit into all these different boxes. Like, I fit into world music, because I have an Indigenous influence in my music, and I always work with a dancer, an Indigenous dancer. So I go to the world music events, and I get the world music gigs. I also get the art festival gigs like Luminato and PuSh, which are a little more all-encompassing. I’ve done the Darwin festival in Australia, as well as the Sydney Fest in Australia. And those are very similar, they’re multidisciplinary festivals. But I also fit into the classical world. I am getting those gigs right now, too — with the Calgary Philharmonic, for example.

This allows me to have such a broad audience base, which is amazing. It helps when you’re building a fan base, but it also enables me to play everywhere, and avoid over-saturating a specific market. Like, I can play in Regina with the Regina Symphony, but I can also play in Regina with the Folk Fest. And those markets don’t really cross over. I’m welcome at both. Being so far out the box kind of puts me in all of the boxes, I guess!

Do you find you interact with those audiences differently on social media and have to post differently to speak to them, or do you just do Cris?

Derksen: I just do Cris. My social media is not really that performative. I have Facebook friends only, I don’t have a Facebook fan page. I took that down because FACTOR [Foundations Assisting Canadian Talent On Recording] and other granting bodies were starting to go in this direction where they really wanted to see how many fans you had. But at that time you could buy fans. And I was like, this doesn’t make any sense for me. I’m here for the music. I’m not here for the fans. I’m here to actually create music for my life. That’s what I want to do with my life. Being famous is not my goal. My goal is to have a long and respected career. You can follow me on Instagram, but you’re mostly going to see my guinea pigs and my dog. Maybe you’ll see like a screen shot of the guinea pig and me composing, but it’s pretty chill. I’m pretty chill when it comes to advertising. I have a website, and I have an agency, and they’re way better at promoting me.

That’s great advice. How do you feel about university music programs and how we might help more diverse students to kind of see themselves here and find pathways to their musical goals?

Derksen: I’ve been having this conversation with my Indigenous peers about how to make university more accessible for Indigenous folks. It’s really tricky, especially within the classical program, because you do need to be at a certain level of performance to get into the program, and that education comes at a younger age. Folks on the Rez definitely don’t get that education. They don’t get a musical education, and all of our governments across the country are constantly taking arts funding out. They need to fund those programs.

At the post-secondary level, one thing I think all universities can do is offer more courses focused on cross-arts and cross-cultural pollination that allow folks from different backgrounds and disciplines to meet each other. I took a course that was really cool at UBC — it was with Dr. Bob [Professor of Composition Robert Pritchard] and Meryn Cadell and Giorgio Magnanensi, all profs from different fields, and it was a multidisciplinary class. That was super helpful. And again, more courses that focus on the business side of things would be really helpful.

As far as getting more BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour] kids into university, I don’t know how to make that more accessible without major changes at the government policy level, because again, the problem starts at the very beginning of their education, when they’re really young.

I did one thing at UBC that was super-cheeky — I took a Master’s level pop theory course. In the course we were discussing all of these different Western theories of art and classical music, and then trying to bring in pop music into it. My first paper for that was like, “We’ve gotta change the language of this theory, because it’s like putting the square peg in the round hole. These things don’t actually connect. If we’re going to talk about Black pop music, we need to ask What is Black theory in music? Like, breaking that down. So I wrote a paper saying that we need to change the language. And then, to make my point clear, I didn’t write my final paper. I’d performed with Kanye West that year, and I just handed them a manila envelope with my invoice for Kanye West. I was like, “This is pop music. This is pop theory.” I didn’t pass, but it is definitely something I still believe, that we need to change the language of music theory.

That’s definitely what I’ve seen at the music theory and musicology conferences in the last two years. There are a lot of people standing up and saying that we’ve got a problem. Finding a new pathway is the challenge: how do you create space for these other musics in what has traditionally been quite a narrow theoretical program.

Derksen: Yeah. But I do feel like things are changing. There are a lot more papers being written about this by people like the composers Andrew Balfour and Ian Cusson.

You and Andrew and Ian were key members in a group of Indigenous artists that met in Banff in 2019. The meeting was Call to Witness: The Future of Indigenous Classical Music. Can you give us an idea a little bit about where that movement is going, and its impact on the Canadian music scene?

Derksen: It came about in response to some gaps within Indigenous music. It’s a vibrant community, especially in the pop and folk scenes, and there are quite a few Indigenous folks working in the classical world, too. But in the classical world we were all kind of working alone. We knew who each other were, but we didn’t actually know each other. Reneltta Arluk, the head of the Banff Centre’s Indigenous Arts programs, approached me about running an event, and I thought this was something we needed to address.

The purpose of the Call to Witness conference was to bring us all together to build these relationships and talk about appropriation in the classical music world. Because, for example, there are still Indigenous projects for symphony getting funded that don’t include Indigenous composers. This is something that we have to take back. These are our stories to tell. If Indigenous stories are going to be told, they need to be told by Indigenous people. Look at a project like — and I’m going to name names here — the Royal Winnipeg Ballet’s Going Home Star. How did that not include Indigenous people at the very top? They didn’t have an Indigenous choreographer, they didn’t have an Indigenous composer. They brought in Tanya [Tagaq], but that’s one throat singer who’s coming in to perform work that’s being written and directed by non-Indigenous people. So that was something we talked about at the conference.

But the conference was really beautiful. We came together for like ten days, and we talked about where we want to shine a light for the future. In the end it’s about creating relationships and friendships within the community, and it’s creating relationships with the institutions, the symphonies, the arts administrators, and the performers. That’s how you make change.

Yeah, I was pretty struck by that as it was happening. I think almost all the artists who were there have really become more evident in Canadian music since then. Regarding your own work, I wonder if we can talk about your Juno-nominated album, Orchestral Powwow. Give us an idea of what kind of musical space you were kind of constructing there.

Derksen: Again this goes back to the grants! [Laughs.] Reading about so many Indigenous projects without an Indigenous lead brought me to this space. It stemmed from me wanting to be like “No, actually let us tell our own stories. Let Indigenous people do classical music. Give us the reins, we’re ready!” With the album, I was coming back to my classical roots, and really, really, really bringing up my Indigenous roots. So, Orchestral Powwow is exactly as it sounds, it’s powwow music with symphonic music written around it. I use the same library that A Tribe Called Red did for powwow music. I kept the powwow pieces full and as they are, and composed around them. That led to a full 45-minute show that still continues to run, surprisingly.

That’s a great concept. The traditional orchestral thing would be for you to take over the role as the conductor. I mean, how did you decide to do it the other way?

Derksen: Well, I wanted to play the solos that I wrote for myself. And I have this conceptual little thing, which is that usually there’s not a conductor, because I feel like usually a conductor is an old white man, and I feel like in Canada we don’t necessarily need to listen to the old white man any longer. The European players have to follow the beat of the Indigenous drum. It’s a metaphor for how I feel that we need to listen to the beat of the Indigenous heart in Canada. And it’s challenging! Powwow music is basically in 4/4, but the confusing part is orchestral musicians always give like one beat, and then they start. So when I’m working with an orchestra, they don’t listen to beat one. For them, that’s not the beat. I’m always having to tell them that beat one is when they start.

There’s always that challenge when you’re negotiating between those different traditions. But I think that’s the place that we’re in now. When we want to open ourselves up to collaborating with people, we need to budget more time. And I think that’s something the arts councils need to think about. Our professional associations, too.

Derksen: Exactly. Exactly.

And now, thanks to the pandemic, we’re all of a sudden in this really different world. How do you think life is going to change over the next two to five years, as we aren’t sure how big our audiences can be, we’re not sure if or when we can even travel. How are musicians going to monetize their incredible skills?

“There are still Indigenous projects for symphony getting funded that don’t include Indigenous composers. This is something that we have to take back… [i]f Indigenous stories are going to be told, they need to be told by Indigenous people.

— Cris Derksen (BMus’07)

Derksen: I feel like it’s going to be more collaborative projects. Working with filmmakers, people from different disciplines, creating art that works in different spaces. Again, now is a great time to go for grants. Go and get them all, right now! [Laughs.] I feel like when there are parameters around anything, and you’ve got to make something that fits within those constraints, you can come up with such creative ideas. COVID has created those constraints. It’s like putting on that creative brain and being like: “What can we still make this very relatable, and how can we still make this feel like community?”

What’s your sense of the relative roles of live performance versus recorded performance as we go forward? Working via video has changed how we think about the way we position at our instruments and lighting and all that kind of stuff, but it’s more than just that. And as we go into a time when it’s more possible to do things live, what do we bring with us from this experience of online performance?

Derksen: The live thing is not ever going to go away because people crave that in-person experience. It’s not the same on the computer. And online, for us as performers, the energy exchange is not there. As soon as I feel like it’s safe to fly, I’m going to perform live again.

I think, though, that there are going to be advancements from this. Livestreams are allowing arts to become a lot more accessible for people who can’t necessarily make it to a live show. The other thing I do like about this new world is that we’re all in the same boat. It’s democratized things. So it doesn’t matter how many performances I’ve done around the world, I’m in the same boat as first-year music students. We’re all learning from this experience together. So I feel like there are advantages for up-and-coming musicians to take the reins and get really creative with what they do!