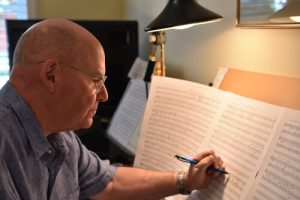

Professor of Composition Dr. Stephen Chatman reflects on his life’s work, teaching at UBC since the 1970s, and retiring during the COVID-19 pandemic

UBC’s Dr. Stephen Chatman

Interview by Tze Liew

Dr. Stephen Chatman, Professor of Composition, is one of Canada’s most prominent, versatile and frequently performed composers. From grand orchestral works, to classic piano gems for learners, to imaginative choral songs that sell 20,000 copies of sheet music a year, his music is beloved by ensembles, choirs and fledgling pianists across North America — praised as “bright, expressive, eminently accessible fare that’s easy on the ear and good for the soul” by the American Record Guide.

Prof. Chatman has been teaching at UBC since 1976. He was the youngest faculty member then, and probably the oldest now. After a whopping 45-year teaching career, during which he has mentored scores of students who have gone on to great careers, Prof. Chatman will retire this year at the age of 71.

High Notes took the opportunity to talk to Prof. Chatman about his adventures as a composer and professor, and hear his perspective on how the music landscape has changed over the years. Dr. Chatman has always been a pillar of inspiration and encouragement to his students — his wellspring of lived experience, musical knowledge and quirky stories will be missed.

On April 15th and 16th be sure to tune into the UBC Bands’ Spring Showcase and the UBC Symphony Orchestra’s season finale, both of which will feature works by Prof. Chatman.

You’re a very prolific composer. What is your process? How do ideas come to you, and how do you so easily turn the germ of an idea into something fully realized?

There is a mystery to composing and, as I get older, I understand less and less about composition. Like many composers, I find that beginning a work is the most difficult. Some parts, like transitions, are more difficult to write than others. But once I have a start, I can usually finish a piece without too many problems. The one piece of advice I give my students is, “Try not to worry about whether your music is good or bad – just write it.” Easier said than done, especially for young composers.

I don’t know how ideas come to me except that they usually come while reading lyrics or improvising on a keyboard. For me, it actually is easier to develop germs than to create the right ones. Incidentally, I must be the only UBC composer who doesn’t use computer software — I hire a copyist / engraver!

Try not to worry about whether your music is good or bad — just write it.

What kinds of music are you most compelled to write and why?

In the 1960s and 70s, academic composers, including me, were strongly influenced by various avant-garde movements. Having composed much “modernist” music as a young composer, my style and aesthetics slowly began to evolve. Minimalist and other composers reacted to the stilted academic-ism of North American university composition departments. For me, beginning in the early 1980s, composing choral music using a predominantly tonal musical language became a compelling new direction, a kind of “release.” It was inevitable that, as my choral music became more and more popular, I gravitated heavily toward commissions for this medium. Simultaneously, my instrumental music evolved but remained complex and eclectic, often characterized by revolving cycles or patterns, poly-tonality, and poly-styles, including older styles. I have always composed whatever excites me.

What do you consider your most important accomplishments? Which works/premieres are you most proud of?

I suppose my most important accomplishment was my appointment to the Order of Canada “as a composer and teacher to a generation of Canadian composers.” I cherish the ongoing invitation to donate my papers to the Library and Archives Canada (LAC) Stephen Chatman fonds. Memorable premieres include major works for large ensembles: Proud Music of the Storm, Crimson Dream, Tara’s Dream, Over Thorns to Stars, Earth Songs, Prairie Dawn, A Song of Joys and Magnificat. Trevor Dearham, a University of Toronto DMA student in conducting, has just finished a major thesis entitled “The Choral-Orchestral Works of Stephen Chatman.”

What’s your origin story as a composer? Who were your favourite composers and how did they inspire you?

Fortunately, I grew up in a musical family. My father was a fine pianist and our home was often the site of live classical chamber music. I began piano lessons at age five and writing little piano pieces at about age eight. Throughout grade school and high school my composing expanded to small and large ensembles. As for favourite composers, the list is extensive. To name only a few: Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, R. Strauss, Ives, Stravinsky, Ravel, Bartok, Crumb, RM Schafer, Reich, Bolcom. They and others inspired me in so many ways that it would take many words to explain. Naturally, a composer’s cultural and musical environment — time and place — affects profoundly.

Moving to Canada by choice, I’ve become a Canadian composer: a lot of my pieces are about nature, and there isn’t a more beautiful place than the province of B.C. A great influence has been my interaction with various ensembles and choirs in the city — the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra, for example, was important to my career at many points. And of course, my colleagues, the performers and composers I’ve worked with throughout the years have influenced and inspired my compositions.

WATCH: Jose Franch-Ballester performs Prof. Chatman’s “Warm Summer Sun”

Tell us about your days as a student.

Prof. Chatman in the 1970s.

I studied at the Oberlin College Conservatory in the late ‘60s — it was a hotbed of music, liberal arts and student protests back then. Almost every significant American and European composer visited the campus. It was a rich, exciting environment. I clearly remember that, as a protest to the Cambodian bombing in the Vietnam War, on May 6th, 1970, the Conservatory decided to perform the Mozart Requiem at the National Cathedral in Washington, DC. Our 300-voice chorus (I was a “tenor”), soloists and orchestra rehearsed May 7th and 8th, traveled in seven buses to Washington on May 9th, and performed in the Cathedral the morning of May 10th!

That same year, Oberlin composition students produced an audio tape as a 70th birthday present for Aaron Copland. Mr. Copland kindly wrote back to us, including a complimentary critique of each piece. I also remember Pierre Boulez conducting the Rite of Spring with the Oberlin Symphony the weekend after Stravinsky died in April 1971.

In 1969 while at Oberlin, I enrolled in the first conservatory electronic music program in the U.S. At that time, it took many hours to create a ten-second piece, produced by text entry into a shared large mainframe computer! My training in composition, theory, history, and performance with its strong emphasis on western classical music, was comprehensive and invaluable. Graduate school at the University of Michigan also was immensely rewarding. And studying with Karlheinz Stockhausen on a Fulbright grant in Cologne (1974) was an unforgettable encounter. I kept a diary of his most outlandish comments.

What parallels do you see between being a student in the 60s and early 70s, and being a student today? Do you find that art and music are being expressed in similarly political ways?

Students in the 60s and early 70s were coping with civil rights, assassinations and the Vietnam War, and there was also the women’s liberation movement. The students at the Oberlin Conservatory were very politically active, liberal and revolutionary — being in the middle of that as an 18-year-old was exciting, but also perilous. It was a strange and difficult time.

But we live in a difficult time now too: students are experiencing Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, reconciliation, human rights and the COVID-19 “war.” At UBC and elsewhere, the fragility of democracies have profoundly affected creativity in music and in the arts. Many student composers are writing pieces inspired by COVID-19 this year. Currently, an undergraduate student of mine is composing a work inspired by the attempted coup in Washington on January 6. Classical music programming today makes a point to address gender and diversity equity. Just as civil rights was a major issue in the 60s, our society, once again, is raising questions about human rights, equality and diversity.

You were appointed to UBC in 1976. What was it like teaching back then?

Prof. Chatman conducting the Contemporary Players, a student ensemble

Teaching at UBC has always been fun and rewarding! In 1976, the Music Department and building were relatively new. That year, I taught just one composition student, a non-major. But the composition program developed quickly; soon after I arrived, we established Contemporary Players, the MMus and DMA in composition and the number of composition majors increased dramatically. The ’70s were different in that music professors and students were on campus all day, attending classes, rehearsals, lessons and conversing informally. Faculty often gathered in the faculty lounge, drinking coffee, smoking and discussing plans for the day. There was a real camaraderie. Teaching loads were considerably heavier. In my first two years, I taught Theory 300, Composition 107, Orchestration (two sections), a large number of tutorial composition students, and co-directed Contemporary Players. During this time, there was a tremendous sense of excitement and support within the UBC musical community. Everyone attended concerts. For example, our first Contemporary Players concert (Stravinsky’s Soldier’s Tale) in 1977 attracted a huge noon audience plus a substantial evening audience.

How has teaching changed from the 70s and 80s to now? How are students different, and how has technology changed how they compose?

For me, teaching orchestration has changed relatively little. Except for the addition of technology, recent repertoire, and new stylistic influences, teaching composition also has changed relatively little. Many composition techniques are universal and timeless. The goal has always been to enlighten and guide students. Every composer has a unique talent and process. It took me about ten years to realize that each student requires a unique teaching approach.

I think technology has had an enormous effect especially within the last twenty years. Instead of using a pencil and manuscript paper, many students begin a composition on their computers. The computer is a useful tool, especially for notation and midi play-back, but there are some drawbacks. For example, some pitfalls are repetition in general, cut and paste, impractical parts and the use of limited traditional rather than non-traditional notation. Until about 2010, most composition students brought pencil sketches to their lessons, which we read at the piano. This was great sight-reading practice! Now, they bring their iPhones and computers.

How has our relationship to the classical music canon changed/has the canon itself changed over the years?

The classical music canon has expanded over the years and our relationship to it may be changing. A recent trend in university music curricula is toward diversity and efforts to increase the study of ethnomusicology. This is a worthy direction. But the danger, in my opinion, is to diminish the classical music canon. The vast majority of the UBC music faculty are classically trained as performers, composers, conductors or researchers. For decades, they have successfully demonstrated their considerable talents relating to the classical music canon. For example, they have established outstanding choral, orchestral, wind ensemble, opera programs and solo careers. According to a recent survey of UBC BMus alumni, students’ highest priority is performance and collaboration. It would be a shame to hinder them in this crucial pursuit.

You’ve met a lot of famous composers in your time. Can you tell us some stories about them?

I’ve met many well-known composers, including Dmitry Kabalevsky, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Aaron Copland, John Adams, William Bolcom, John Cage, Ellen Taaffe Zwilich, and dozens of prominent Canadian composers. UBC guest composers over the years include Luciano Berio, Thea Musgrave, Philip Glass, Morton Feldman, George Crumb, Lou Harrison, Rodion Shchedrin, Frank Ticheli, John Corigliano, Peter Maxwell Davies, Leslie Bassett and Ross Lee Finney. I also briefly corresponded with Dmitri Shostakovich in 1970 when I was a student. I invited him to come to Oberlin, and he wrote back in Russian, saying that his health wasn’t good, but he would like to visit me and my students. He thought I was a professor!

Other memorable experiences: as a composition student at Interlochen, Michigan in 1966, we presented a concert of our works, which included flushing a toilet off-stage and throwing ping pong balls into the piano. A guest composer, Zoltán Kodály, was in the audience. During the post concert discussion, faculty members urged Mr. Kodály to critique the pieces. His response was something like: “Béla Bartók and I always supported young composers and experimentation.” To us he was a hero!

Here’s another one: I was the President of Vancouver New Music and we invited John Cage to give a recital at the Cultural Centre. He arrived in Vancouver for a Sunday night concert. On Saturday morning I got a phone call from a professor in the UBC Botany department. He said: “This man named John contacted me because he wanted to go on a field trip to look for ferns in the Endowment Lands.” You may not know this, but John Cage had a real interest in mushrooms — he made quite a lot of money on the subject in an Italian quiz show. I didn’t know that he liked ferns as well, but obviously he did. Anyway, the other part of the story is, some of the composition students showed him their scores, and his reaction was: “I think you’re studying too much theory.”

WATCH: UBC Symphony Orchestra performs “A Song of Joys”

What are some of your most memorable experiences working with performers and ensembles?

I have worked with so many outstanding performers and ensembles, including contralto Maureen Forrester, baritone Tyler Duncan (BMus’98), violinist Andrew Dawes, pianists Marc-Andre Hamelin, UBC’s Patricia Hoy and Jane Coop, and the Verdehr Trio. These performers have premiered my works with stunning musicianship. Working with the conductor, Gunther Herbig, in performances of my Crimson Dream (1982) by the VSO, Toronto Symphony and several American and European orchestras stands out, as does composing several works for the VSO with conductor Sergiu Comissiona in the 1990s. I cherish my long and extensive association with Jon Washburn and the Vancouver Chamber Choir.

More recently, it has been a pleasure to work with my UBC colleagues, Jose Franch-Ballester, Valerie Whitney, Eric Wilson, Corey Hamm, Terence Dawson, Julia Nolan and David Gillham. I especially appreciate my relationship with our UBC conductors Jonathan Girard, Graeme Langager, Bruce Pullan, Jesse Read and Robert Taylor, who have supported me through superb performances and recordings of my works.

You’ve worked a lot with choral music and text setting with your wife Tara Wohlberg, who is a poet/librettist. What do you love about it, and what is the process like?

You might imagine that Tara and I have great chemistry! I love everything about it. We wrote a comic opera, Choir Practice, and have collaborated many times on vocal and choral works. Typically, we agree on a theme and she writes 20 or 30 lines of poetry or lyrics. The words come first. Then I pick and choose lines as I am composing, often changing the order of lines and also the words — but only with her final say! The only exception to this process is that, more than once, Tara has had to replace other poets’ texts for existing pieces, due to copyright problems. Other poets whose poetry I often have set include Christina Rossetti, Walt Whitman and Sara Teasdale. The meaning, direct language and sound of this poetry inspires me.

Looking back on your career of over 50 years, what are the major turning points and important decisions you’ve made?

The best advice I can give any composer is to compose what you love, no matter the style, aesthetic or technique. Honest expression will shine.

There are always major forks in the road. My first important decision, as a student at the Oberlin Conservatory, was to change my major from piano to composition. I never looked back. Attending graduate school at the University of Michigan turned out to be a great choice. But my most important decision was to accept a professorship at UBC in 1976 and immigrate to Canada. Another turning point was turning down a job interview at the Eastman School in 1980 and staying at UBC, because I thought there was a real opportunity to build a composition program here. In hindsight, it was absolutely the right decision. Long ago, I became a Canadian composer and owe whatever success I have had to UBC and Canada. Creatively, a turning point was my work, Proud Music of the Storm for large choir and orchestra (2002). This was the first of several works for this medium.

It’s been a strange year with the pandemic. How do you feel about retiring this year, and what do you look forward to after retirement? How are you staying upbeat with composition, and what will you be working on next?

Last year when I decided to retire, I hadn’t realized 2020-21 would be such a weird year. Needless to say, it’s been difficult for everyone, but especially for students. At 71, after 45 years teaching at UBC, it’s time to retire, to move on with my life, and I feel really good about it. I look forward to more free time; we look forward to travel when it becomes possible.

It’s easy to stay upbeat with composition. Last summer I composed about fifteen choral and instrumental works inspired by the pandemic, including a piece for Jose Franch-Ballester and the UBC University Singers, two works that were premiered by the Vancouver Chamber Choir, a virtuosic solo horn piece called “Courage” for Valerie Whitney, and more. I’m not sure what my next piece will be — perhaps a woodwind quintet, or more choral pieces. I definitely want to do a Book Two of Piano Etudes.

What advice do you have for composers today? Anything you wish you could’ve told yourself as a young composer?

The best advice I can give any composer is to compose what you love, no matter the style, aesthetic or technique. Honest expression will shine. Work hard and take advantage of any opportunities. As one of my colleagues used to say, “there is a strong relationship between the seat of the pants and the seat of the chair.” As to my experience as a young composer, I have no regrets. I was unbelievably lucky — and am most grateful.

Chatman 360°: Former students reflect on Prof. Chatman’s career and influence

Prof. Bob Pritchard

I remember when Dr. Chatman arrived at UBC in the 1970s and he was assigned to teach our 3rd year music theory course. He had a huge knowledge of 20th century composers through to the 1970s, their styles and techniques, their connections, and their repertoire, and he had us carrying out various compositional and analytical exercises which was greatly beneficial for my development as a composer.

Early on in the course before a class, I wrote a limerick on the blackboard about the previous lecture’s topic, attempting to pull things together as a way of remembering things.

Of course, once this started, it had to keep going, so for the rest of the course before each class I would scribble a limerick on a side blackboard and the class would begin with Dr. Chatman commenting on the limerick as being good, off topic, or just plain terrible! Here’s a limerick about that:

A new prof named Chatman taught theory

To students each morn who were bleary.

Bob added his wit:

A limerick was writ

And the prof judged it good, bad, or dreary!

— Dr. Bob Pritchard, Associate Professor of Music Technology

John Korsrud

Dr. Stephen Chatman was my first composition instructor, and was the conductor of the UBC Contemporary Players, in which I played trumpet. I quote him often to my composition students:

“Write what’s loudest in your head, that will be your best music. And once you have a good idea, grab it by the tail and never let it go.”

Dr. Chatman encouraged me to write for the New Music Ensemble which was exciting, and by showing me to Witold Lutosławski, I understood how improvisation could be mixed with notation in a fresh way. That day was my “eureka” moment that propelled me for years. Thank you Steve!

— John Korsrud (BMus’89), composer, producer, trumpet player and leader of Hard Rubber Orchestra

Juno Award-winning composer Jocelyn Morlock

I met Dr. Stephen Chatman when I first came to UBC to study Composition in 1994. I knew his music well from recordings and I was very excited, if slightly terrified, to start a composition degree with him. I’d just moved here from Brandon, MB, and was daunted at the prospect of living in a big city where I knew almost no one, after living in Brandon, whose motto at the time was “40,000 friendly folks.”

But when I went to my first lesson with Steve, he said to me, “I think you know Tara Wohlberg.” I looked at him in puzzlement; it turned out that his wife Tara was someone I’d known in Brandon, before she moved to England to further her studies, and unbeknownst to me she’d since relocated to Vancouver and met Steve!

From the start UBC seemed like a small and friendly world due to their kindness. Studying with Stephen Chatman, there are two things that I particularly recall him saying: first, always write to the strengths of the players. Work with them – better to write something that sounds hard and is easy to play, than sounds easy and is difficult to play. Second, write whatever’s loudest in your head. I took these suggestions to heart, and I must say they are exceptionally good advice that I keep in mind to this day. Thank you Steve, and happy retirement — though I know you’ll keep writing up a storm despite “retiring”!

— Dr. Jocelyn Morlock, Juno-Award winning composer and UBC faculty

Dr. Larry Nickel

Finally retiring? Ha!

While in my third year at UBC, working on a BMus in 1976, I was a long-haired hippy playing honky-tonk jazz in a piano room. There was a knock at the door and someone poked his head in to ask, “What’s that? Did you write that? Wow, it’s really good.” That was Dr. Chatman, new on staff. My first encounter with Steve was life-affirming. During my ensuing years as a teacher I presented many Chatman compositions with my choirs. In 2003, after our children had flown the coop, Edna and I were ready for a new adventure. “Let’s go back to school!” I wanted to study with Steve, and guess what? He remembered me! Working on a DMA in composition with Steve was a blast. I endeavoured to be prepared for the weekly sessions. Steve was very kind and yet candid. “Larry, this section doesn’t really work, does it?” I’d go back to the drawing board and try to fix things. The next week Steve said, “What? you changed things?! Yes, this is better but, Larry, you are one of the very few students who actually listens to me!”

I doubt that, but I imagine some composers aren’t used to having their work critiqued. But that’s why I returned to school – to make some progress – and Chatman was my benevolent mentor. He guided me through my very ambitious thesis, “Requiem for Peace” in 13 languages. The opus recently had its 27th performance, this time at the National Philharmonic of Ukraine. Thanks, Dr. Chatman!

— Dr. Larry Nickel (BMus’77, DMA’06), Owner of Cypress Choral Music and Associate Composer of the Canadian Music Centre

Grace Jong Eun Lee

Dr. Chatman taught me to become a true composer. He always respected his students’ abilities and genuinely wanted to help them to improve. He writes a lot of beautiful music about love, and that has really inspired my music. I applaud his tremendous devotion, passion and dedication that makes him one of the best composers in North America.

— Grace Jong Eun Lee (BMus’95, MMus’98), President of Grace Music College and the Canada Korea Cultural Exchange Entertainment Society

John Estacio

Stephen, congratulations on your illustrious career teaching and composing at UBC. You have been a beacon to many composers. You reminded me that a composer could develop a career as a working professional. For many of us, you might have been the first composer we ever met who was published, and whose music was performed successfully internationally; you showed us there were opportunities and possibilities beyond our little studios. I always enjoyed your camaraderie and your frankness, and perhaps your most helpful piece of advice: “If you don’t know how to finish your composition, look earlier in the piece – the answer is there.” Enjoy your time off doing whatever it is that pleases you the most.

— John Estacio (BMus’91), Juno Award-nominated composer